Journey of Acceptance

|

To

write about one’s present or even venture into one’s future, there must be a

recognition and acknowledgement of the past. That is called maturity, that is

called acceptance, that is called forgiveness. I envision this blog series to

be a bounty of people, events, and reflections of the stories that brought me

to this place in my time. Personal crossroads appear because of the richness of

the journey.

When

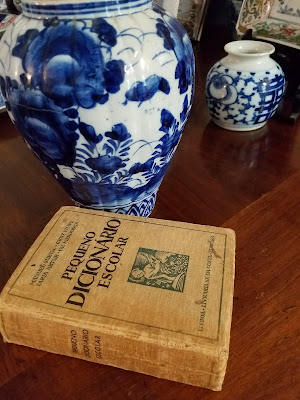

I moved to Sacramento, I unpacked a box filled with a treasure of old bound

books. Amongst them, I found my Mother’s Portuguese dictionary. In her

handwriting she had signed and dated it: Maria Theresa Baptista, 24.11.1944,

Hong Kong B.C.C. She was 14 years old. Its

cover is now fraying and its pages stained with age. Ah, but within its well

utilized pages, there belied the story of family and heritage

Our

ancestry is Macanese--Portuguese of Macao, a Portuguese colony founded by explorers

from the time of Henry the Navigator, Magellan, and DeGama. These descendants

came to be known as the “Macs”. In their proudest moments, I would hear my

Mother, Aunts, and Uncles speak of Portugal and how our ancestors left the

harbor of Lisbon to explore foreign lands. There were also ancestors from Italy

and Holland… some of the countries that went in search of conquest and

colonization. I was told stories about streets in Macao named after famous

ancestors.

Though

the Portuguese eventually settled throughout Asia—the majority moved down the

delta to Hong Kong. For generations, my

family lived in Hong Kong, a British Crown Colony. As a child, I came to

envision their Hong Kong as it was pictured in the film, “Love Is A Many

Splendored Thing”. I imagined it to be

filled with beaches, ferry boats floating on a bay dotted with sampans that sat

before a rising skyline, with lots of gardens and quaint, cobbled streets. Proud

British police in their khaki shorts would ride in rickshaws to lunch at the

Peninsula Hotel.

Though

Portuguese by heritage, the Macs also revered the English as they saw

themselves as loyal subjects of the British Commonwealth. Long live the

queen! They never questioned as they

would take their place “below” the English, working primarily as the accountants,

teachers, etc. in the socio-economic structure of the colony.

|

| Ah Yee and me |

There

was also a huge Chinese population. After all, they were there first. Before

ANY European intrusion. But for so many centuries, it was accepted that they

were the “amahs”, the servants. When I was born, even I had my very own amah.

She was referred to simply as Ah Yut. #1 servant. When my brother was born, he

was cared for by Ah Yee (#2), then followed by Ah Sam (#3) for my youngest

brother. That was the life in the colony. That was the world of my parents and

those who came before them. Centuries of confusing allegiance to the romanticized

Portuguese Motherland, the English oppressive colonial rule, and the minimization

of the Chinese. It was a caste system that muddled social interactions and ultimately

paralyzed hierarchal mobility. And its ramifications on the personal stories

are truly worthy of a Michener saga.

One

photo in particular imprints and explains…one my Mother had on a mantle in the

living room. In the greying, fading patina of this intriguing portraiture are

rows of little girls placed in social ranking, perhaps intentionally or perhaps

naturally as an unconscious acquiescence. The bottom row clearly shows girls of

Asian descent, wearing simple Chinese amah garb of black pants and white

tunics. In the middle row stood the Portuguese girls—a mixture of darkened faces

that seemed racially undefinable. My Mother stood in this row. They wore more

Westernized dresses, clearly hand sewn and perhaps handed down from sister to

sister—yet there was a prettiness and pride that each was wearing their “best”.

And on the last row were the English girls in lovely frocks and large bows in

their blonde hair, flanked on either side by dashingly handsome and tall

British gentlemen,each dressed in suit and tie.

“What

is happening in this photo, Mom? What are these little girls doing?” I asked. My

Mother told me about a famous British trading company. They were having a party

for all the local children. These were the girls who attended.

“So

did you play with them, were they your friends?”

She

seemed startled but then simply explained, “No, I only spoke with the

Portuguese girls in the middle row…we all knew our place”.

A

side bar…when World War 2 began, Hong Kong which, as noted, was English.

England was an Allied country and at war with Japan which promptly began

invading/bombing Hong Kong. The Portuguese community fled to Macao, which, as a

Portuguese colony, remained neutral. The Portuguese government did accept them

as refugees but relegated them to very dire living situations. The Chinese were left behind to suffer the

direct ravages of war and the British fled back to England. But not all escaped.

Many of the British were put into Japanese concentration camps. As the story

goes…three of the English girls in that very photo, in that last row with their

fairy tale dresses, were being transported in a Japanese freighter to one of

those camps. Their boat was bombed and it rapidly began to sink, leaving the

survivors flailing in the water. As they swam for their lives, the girls were

shot by their Japanese captors to ensure they could not escape.

In

war, there is no mercy for privilege.

After surviving the war and back in Hong Kong, the “Macs” seemed to realize the potential "threat" of communism from China. It was the early 1950’s. Having experienced that neither the British or Portuguese would really protect them, they began a slow emigration--primarily to America, Canada, Australia, and England. Today, Hong Kong is no longer a British colony. It was given back to the Chinese, rather peacefully and matter of factly. Towering skyscrapers prevail and the landmarks that marked the lives of my family are either gone or dwarfed amongst the newness of the bursting boom. Macao is now a gambling mecca and the cobbled streets and old homes have vanished. And there are very few Macs left in either place.

|

| At Kai Tek Airport, the day we left Hong Kong, with family and friends saying good-bye |

|

| Growing up in San Francisco |

At

the same time, I was growing up. I struggled with

my legacy. I came to see myself as American. It was easier than explaining all

that colonization and conquering “stuff”. And I created my own childhood memories that

were defined by neighborhood and the city that surrounded it. And I came to see

myself as simply an American. I became that little girl who started each school

day with the Pledge of Allegiance and was proud of her new country. This

evolution was necessary assimilation and acceptance – and a concerted effort to

leave the past behind. The immigration process is the most challenging for the

very first generation that must ultimately figure everything out and forge a

new life.

I

will never go back to Hong Kong or Macao. The lifelong immersion with the

legacy has been overpowering enough. One of

my cousins once told me to forget about Hong Kong; it was not the glamourous

place our parents romanticized incessantly about. It was and is a mess. Just

move on. For many, many years, I thought she is right.

Then…when

my youngest daughter graduated from college, she announced that she was going

to visit Hong Kong and Macau. “I am going to find out what you did not tell

me.” I was shocked and responded defensively. I thought I was protecting her

from the confusion. I thought I had raised her free from the shackles of the

past and that I had presented her a good life neatly wrapped in Americana. But she went and,

ultimately, I found myself very, very proud of her.

Then

Mom died. It was and continues to be an immeasurable void. It is not just the

enormity of losing your Mother but it also is a grieving process of

understanding who and why she was. As I

went through her things, I found her diary, her photographs, her special vases,

the dress she wore as she left for her honeymoon. And with each artifact, with

every word I read, I finally understood. I came to see that my love for her did

include that young girl who carried that Portuguese dictionary as she walked to

school in a dress she inherited from her sister. I came to understand why she felt obligated to

stand in the middle row of that picture. I came to forgive her for not letting

go of the world she loved while I was trying to make sense of it all. It has

been an incredible journey of acceptance.

|

| My grandaughter presenting her heritage to her classmates. Her younger sister looks on. |

And

deep in my heart, I sensed that the ancestors were smiling—especially Mom.

|

| Ancestors, taken in Hong Kong in the late 1800's |

|

| My Mother (standing on the far left, second row) and her family, Circa early 1940s |

|

| Me, age 3 and my Hong Kong Days |

|

| My grandmother, Elfrida |

|

| Mom and me in Hong Kong |

Wonderful!

ReplyDeleteThank you!

Delete